Not so long ago I came to the intriguing realisation that, this year at the cinema, I have seen more classic films than new ones. To be exact, 13 classics and 10 contemporary films. Such a feat is easily accomplished in London, where the herculean BFI and the Prince Charles Cinema show thousands of classics year upon year, often in original, well-scratched 35mm prints. Yet it still seems a remarkably unusual thing to have discovered; one which suggests certain truths about my personal relationship with cinema and of the films I cherish in particular.

What is a “classic”? The US Library of Congress, which selects up to twenty-five American films each year for preservation, claims that ‘culturally, aesthetically or historically significant” values are most important. American Graffiti (1973), Ben-Hur (1959), Groundhog Day (1993) and hundreds of others are thus granted an auspicious status that in many circles commands the use of the word “classic”. Or is a classic a far more subjective thing? To most who have seen it, the Russian film Andrei Rublev (1966) is an inevitable classic because of its masterful cinematography and compelling performances; a film that evokes Medieval spiritual life with astonishing panache. To a few dissenters, however, it is an episodic and loose monster in which not a lot happens at all, and so the honour of being a “classic” is disputed.

Shallow postmodern arguments aside, what does strike me is the fact that most of the films I’ve been seeing in cinemas this year are significantly old. The last screening I attended was The Wild Bunch, released in 1969. The film I’m most looking forward to this September is not something new; it’s Fritz Lang’s M, first shown in 1931 and about to be re-released. As my interest in cinema deepens, the further back my enquiries take me – back even to the early stages of the medium itself, with my recent discovery of George Méliès’ La Voyage Dans La Lune, a beautifully detailed science-fiction short released in 1902.

Many of my friends and peers who love cinema share this interest in “old” films, yet not many venture to the BFI or Prince Charles, preferring the ease of a DVD. This was evidenced frequently in my mid-teens, when I once found myself sitting in a screening of Jean Vigo’s L’Atalante (1934) as the youngest audience member by some thirty years. Perhaps that was just a bad day for youthful representation. But sometimes I do wonder if my friends could gain something from taking their interest in “old” films right into the heart of the very places they were first shown: in a hushed screening room, pitch dark, the screen the only light source – a place where cinematic sorcery is experienced at its most thrilling and palpable. If you try hard enough, you can really imagine what those first audience members must have thought and felt. Seeing old films in the cinema emphatically makes a difference, and broadens your view of the medium’s possibilities.

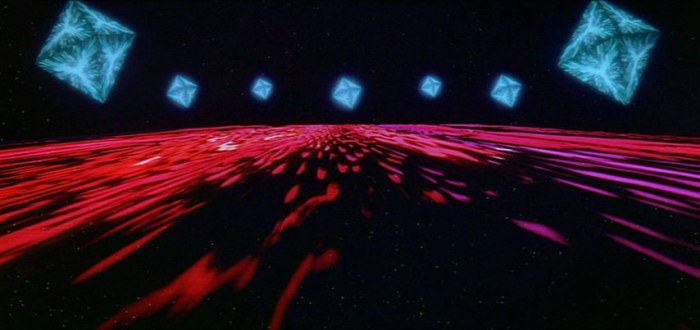

There’s also the question of the character of contemporary cinema. It’s singularly useless to argue that filmmakers like Michael Bay and the endless train of sequels and remakes have rendered cinema dead, although it’s easy to think so. In fact, nationwide festivals, especially the London Film Festival, continue to grow year upon year in exhibiting serious-minded, artistically precise films. The Curzon and Picturehouse chains are great places to find the latest arthouse dramas and comedies from all over the world; both are opening new cinemas across the UK. Yet my status as a soon-to-be History student has influenced my thinking; I’m convinced that in order to better understand contemporary cinema, I have to journey back into the past to see exactly where it has been. The roots of most modern science-fiction films with pretensions to artistic merit can be traced back to 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Black Swan (2010) seems all the less significant when compared to The Red Shoes, which accomplished much of what Aronofsky’s film did, only sixty-two years prior. Every film has a precursor, and I’m fascinated by trying to find such films and assessing their formidable influence over time.

Looking at it this way, the surprise at having seen more classics than contemporary films really shouldn’t really exist. What’s more, it could be said that the “old” films I’m growingly obsessed with, with all their vibrant and diverse cinematic qualities, are in fact profoundly new.