This year’s London Film Festival felt paradoxically both busier and quieter than usual. Busier because audience numbers just seem to grow and grow, with most screenings eventually selling out completely. (This was great news for the festival organisers, though rather less good for the legions of people battling to get tickets to the one screening of Chicken Run: Dawn of the Nugget.) Quieter because members of the acting union SAG-AFTRA are still on strike over wages and conditions, and few if any actors were to be seen on the red carpet.

The absence of actors meant a different sort of discussion at pre-film introductions and post-film Q+As. The emphasis was on screenwriting, directing, music, and visual style, rather than on character and performance. For someone who has always been more interested in the people behind the camera than those in front, this was a welcome shift, though I hope a temporary one. Many of the films I saw this year will be distributed by Netflix, which alongside other streaming companies has been a major cause of both the writers’ and actors’ strikes (largely because of their stingy remuneration policies and dabbling with AI). Indeed, while small production companies like Aardman incited warm cheers or nods of appreciation from the festival audience, the Netflix logo was met with stony silence and the occasional boo.

The streaming services do, of course, give directors a greater degree of freedom than many traditional production companies; it’s unlikely that Martin Scorsese could have made Killers of the Flower Moon, a festival hit running to three-and-a-half hours, without funding from Apple TV. But sometimes this comes at a cost: Netflix allows its new releases little more than a few weeks in cinemas before they become mere “content” on its platform, to be absorbed in whatever form the viewer wishes. This is farcical: if LFF 2023 taught me anything, it was the continuing vitality and importance of the big screen. Put simply, nothing compares to the shared experience of the cinema, and the festival’s growing popularity suggests that many still agree.

This year, I saw 16 films. Here’s what I thought of them.

“Yes, we are all individuals”

I kicked off the festival with David Fincher’s The Killer (★★★★★), one of many films portraying highly distinctive and unusual characters. The killer of the title is an assassin-for-hire, played by Michael Fassbender, who is fastidious about doing his job properly and leaving no trace. He lives by the motto “Stick to the plan. Anticipate, don’t improvise,” but when one of his assignments goes wrong, his tightly controlled world begins to unravel. The shadowy cinematography, pulsating music and increasingly frantic editing brilliantly evoke the killer’s vigilance and anxiety. It’s a real nerve-shredder, but with great wit and detachment: Fassbender’s character narrates the story in the manner of a classic film noir – knowing, ironic, wryly amused. While waiting for his targets to appear, he passes the time by listening to The Smiths and practising yoga. It’s a terrific, full-blooded performance, and Fincher’s best film since The Social Network.

A rather different sort of (non-)assassin is on display in Hit Man (★★★★☆), which is further evidence of director Richard Linklater’s talent for creating great characters. Star and co-writer Glen Powell plays Gary Johnson, a Philosophy professor at the University of New Orleans, who spends some of his time working for the city police. He begins posing as a gun-for-hire to lure unsuspecting would-be murderers into the hands of the cops. And then he falls in love… It’s partly based on a true story, though with a rather freewheeling approach to key details – all part of the fun – and balances moments of incredible tension with gasp-inducing comedy. I saw this on a Wednesday afternoon and I would happily have spent another hour in the company of its characters.

The same could be said for Molli and Max in the Future (★★★★★), one of the great discoveries of this year’s festival. The film takes place in a future universe which echoes the rainy, overbuilt, media-saturated cityscapes of Blade Runner and The Fifth Element. Its characters are sentient robots, demigods, and aliens. And yet they talk and behave like highly-strung New Yorkers who spend all their time philosophising in bars and complaining about their therapists. It’s essentially a sci-fi retelling of When Harry Met Sally, with the two main characters falling in and out of each other’s lives over the course of many years. Except, of course, one of the characters is a half-man-half-fish hybrid, and the other is able to fly. The joy and hilarity of the film come from how brilliantly it riffs on our messy modern lives. There are nods to social media, online dating, and even Donald Trump, while the attention to detail is astonishing: packages are delivered by Amazon Slime, while one of the characters keeps a book by Sally Rooney called Normal Aliens. I laughed uproariously but also gasped at its visual ambition: the film was made with a tiny budget and skeleton crew, but uses practical and visual effects to create a world that is just as stunningly realised as any contemporary blockbuster. But despite the intergalactic setting, the characters still feel down-to-earth: I found myself rooting for the central couple, sharing in their joys and pains, and hoping that they would end up together. It’s the debut feature of US filmmaker Michael Lukk Litwak and I thought it was magnificent.

Another debut was rather less successful. Poolman (★☆☆☆☆) is Chris Pine’s attempt to capture the noirish atmosphere of The Big Lebowski and Chinatown, but without the skill, wit, or originality of either. It follows a lazy swimming pool technician who uncovers a trail of corruption linked to the local government of Los Angeles. The cast is promising, but they are wasted on a poorly-disciplined script, executed with no comic timing at all. I found it side-splittingly unfunny and a bizarre disappointment.

Filmception

As ever, I saw several films this year that reflected in some way the art of filmmaking. The best of these by some distance was Cobweb (★★★★☆), a South Korean farce about a director in the 1970s who tries to do two days of reshoots on his horror film. The director – engagingly played by Song Kang-ho – is convinced that he is creating a masterpiece, but he hasn’t reckoned on the simmering resentments emerging between his actors and crew. Moreover, he hasn’t told the government censors about the reshoots, which puts the whole studio in danger of being shut down. The film satirises the South Korean film industry in the 70s, and the ways in which the creative industries chafed under authoritarian rule. It’s also a wonderfully funny and tightly constructed farce, with more than a hint of Noises Off as the film crew’s foibles lead from one disaster to another. If that wasn’t enough, it’s also a stirring portrayal of creative passion and our collective love of cinema that left me grinning from ear to ear.

Creative passion was also at the heart of Croma Kid (★★★☆☆), surely the only offbeat sci-fi drama from the Dominican Republic I am likely to see this year. Set in the 90s, it follows a family who make eccentric public-access TV programmes using green-screen effects. It’s a vibrant and colourful evocation of the Dominican setting, but it takes a while to get going; its enigmatic and low-key style is most effective in the final third. Equally enigmatic and low-key was Close Your Eyes (★★★☆☆), only the fourth feature film made in fifty years by legendary Spanish director Victor Erice. I love Erice’s first two films, which are a beguiling combination of painterly cinematography, subtle, often near-silent sound design, and a keen sense of magical realism. His latest follows a former director who searches for an actor friend who went missing years ago – a wry comment, perhaps, on Erice’s own absence from filmmaking. The opening – part of an incomplete film-within-a-film – is Erice’s style at its best, and the ending is a hugely affecting paean to the interrelationship of cinema, time, and memory. Yet much of what happens in between is baggy, rambling, and comparatively pedestrian in style. At times I found myself wishing that I was watching the film-within-a-film, rather than the modern-day story. There are meaningful moments and ideas, but it could have been much more powerful if it were half an hour shorter.

Global Visions

The London Film Festival is always a great moment to opportunity to catch up on world cinema, especially from countries whose culture we may know little about. If Only I Could Hibernate (★★★★☆) is only the second film I have seen from Mongolia, but its story and milieu are quite some way from the vast plains and nomadic culture usually associated with the country. This is a decidedly urban film, one which takes place in the city’s impoverished suburbs. It follows a teenage boy who is trying desperately to provide for his family, who all live in a small yurt, while also attempting to succeed academically. The tension between his two goals only deepens as winter drags on and he struggles to afford coal and wood. The film explores the issue of air pollution with great subtlety and nuance – the characters suffer unexplained respiratory illnesses, and the camera brilliantly captures the thick smog that hangs over Ulaanbaatar like ethereal prison bars. There’s similar care taken in its portrayal of wealth disparities, and on the varying effects of extreme cold. But first-time director Zoljargal Purevdash also ensures that there’s something to root for: the central character’s pursuit of a National Physics competition is a wonderful paean to the transformative value of education. The film – beautifully shot, sincere, political – heralds a compelling new voice in world cinema.

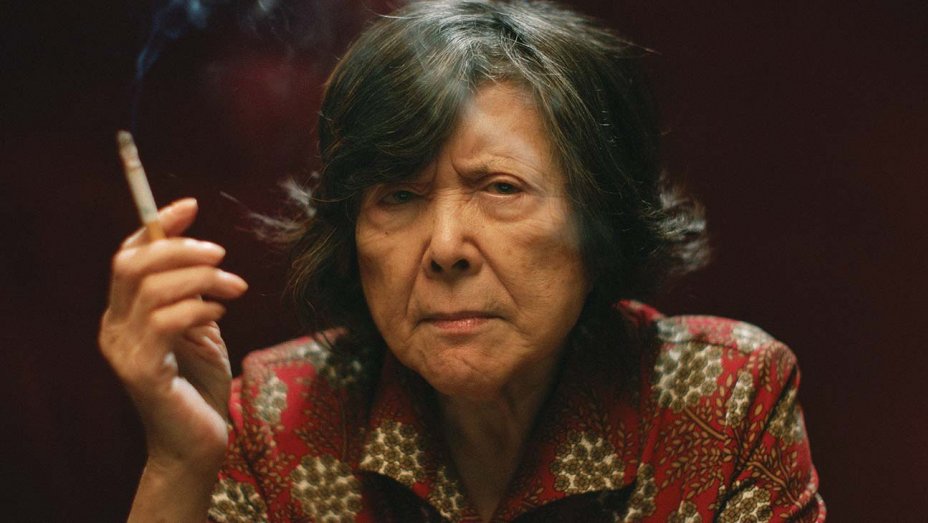

An equally misty setting pervades Only the River Flows (★★★☆☆), an enigmatic, slow-burn Chinese mystery about a detective investigating a set of interlinked murders in rural China in the 1990s. The 16mm cinematography emphasises the hazy, noirish atmosphere, much of which feels like a cigarette smoke-infused dream. The plotting is a little uneven, but I enjoyed getting lost in the darkness. Behind the Mountains (★★☆☆☆) also left me feeling rather lost, though in a much less positive sense. The film tells the story of a mentally unstable Tunisian man who takes his son into the mountains, for reasons which increasingly border on the magical. There are moments of transcendence, but it can’t quite decide on a particular mood or approach, and I found it a bit directionless.

Fun for all the family

For many at the festival, the main event was the world premiere of Chicken Run: Dawn of the Nugget (★★★★☆), a full 23 years after the release of the original film. Aardman rarely disappoint, and their painstaking attention to stop-motion detail and anarchic, very British sense of humour are on full display here. Where the first film was an escape movie, this is more of a heist film, with all the high-tech trappings of a James Bond film. The film follows the crew from the first film – albeit with several changes to the voice actors – as they seek to recover something stolen from them. It may not be as good as the first film, but it’s still streets ahead of the competition when it comes to animated children’s films. I found it joyful and uproariously funny, shot through with an uplifting feminist message; further evidence of Aardman’s position as an essential part of our cinematic heritage.

Rather different in tone was the latest – and perhaps final – film by Hayao Miyazaki, the Japanese master director of some of the greatest animated films ever made, including Spirited Away and Princess Mononoke. The 82-year-old Miyazaki has threatened to retire on at least four separate occasions, but The Boy and the Heron (★★★★☆) further demonstrates his astonishing creative energy. Much like his other films, this one focuses on a child who learns to deal with traumatic events by an interaction with a fantastical world. The film is just as beautifully layered and elegantly enticing as ever, inhabited by strange magical creatures, and imbued with lyricism. The meaning of the film isn’t very easy to divine – additional viewings are surely necessary to unwrap its mysteries – and it didn’t feel quite as consistent as some of his other works. But as sheer experience, it immerses you in its world like a dazzling kaleidoscope.

The word “dazzling” also came to mind during The Black Pirate (★★★★☆), a classic 1926 silent film which was part of LFF’s “Archive” strand. It’s an agreeably straightforward aquatic adventure, awash with swashbuckling, romance, and a range of rambunctious characters. The dashing Douglas Fairbanks pulls off some genuinely thrilling stunts, which on this occasion were accompanied on live piano by the supremely talented Neil Brand. What makes it more distinctive than other pirate-themed silent films is its very early use of technicolor cinematography. Following a new restoration by New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the colours really do pop out of the screen – I gasped as the first image came up.

Based on true events

The final three films I saw were all based to some extent on a true story, although with very different cinematic approaches. The rousing sports biopic Nyad (★★★★☆) has a winningly unconventional subject: a woman in her 60s who attempts to swim between Cuba and Florida, a distance of some 110 miles awash with sharks, box jellyfish, and potentially fatal weather. Swimming, happily, is one of the few sports in which age is not a significant barrier to achievement. Played by Annette Bening, Diana Nyad is a force of nature, single-minded in her pursuit of a successful swim, even if it alienates those she loves the most. There’s a remarkable verisimilitude in her performance, with her body and face convincingly reflecting the mental and physical privations of the swim. The filmmakers also made The Rescue, about the efforts to save a Thai children’s football team from a flooded cave system, and the editing here is similarly breathless, with real archive footage interwoven with fictional scenes. Some may feel that some scenes of trauma are too summarily dealt with, but it is the kind of film that makes you want to punch the air – and put on a swimming cap.

Where Nyad is a predominantly exterior film, The Goldman Case (★★★★☆) takes place almost exclusively inside a small courtroom. The film’s dialogue is based on transcripts from the 1976 trial of Pierre Goldman, a French left-wing activist and provocateur who was charged with several robberies and the murder of two pharmacists. Arieh Worthalter gives a magnetic performance as the charismatic Goldman, who insults the prosecution, taunts witnesses, and launches diatribes against police racism and corruption. It deals with big themes that are sadly still relevant in contemporary France, including antisemitism – Goldman was Jewish – and the gaps in France’s understanding of race and ethnicity. Despite the limitations of its setting, I found it absolutely riveting.

Just as riveting, though much less dialogue-heavy, was The Zone of Interest (★★★★★), the best film I saw at this year’s festival. It’s a masterwork of extraordinary power and ambition by the British director Jonathan Glazer – a film about the Holocaust, but with a very distinctive visual focus. It takes place in a house bordering the Auschwitz concentration camp, occupied by camp commandant Rudolf Höss and his wife and children. The Höss family lead an apparently bucolic existence of horse-riding, gardening, and swimming, largely oblivious – or indifferent – to the mass slaughter taking place mere metres away. We seldom, if ever, set foot inside the camp, but expressive wide shots and unsettling sound design remind us of its horrors. Auschwitz’s barbed-wire walls adjoin the family garden, and Höss’s wife blandly tells her mother that they have planted some bushes to make them prettier. The delighted screams of children playing intermingle with the faint roar of SS guards. Höss smokes a cigar at night, his back turned to one of Auschwitz’s chimneys shooting out smoke from a gas chamber. Formally Glazer keeps a cool distance from the characters – there are no close-ups – echoing the mechanistic detachment of Nazi guards. It is a film that reminds us that the monstrousness of the Holocaust was to be found not just inside the camps themselves, but in the dinner parties, lounges, and gardens of Nazi oppressors – in their relentless insistence on normality, unburdened by the bloody work of genocide. As an artistic statement on the banality of evil – and as an example of how events offscreen can be far more frightening than events onscreen – it is simply staggering, and unlike anything I have seen before.